Modern Science Changes Football Tackling Techniques

For years, the instruction on how to make a tackle was straightforward, almost primal. It was about being the harder hitter, about imposing your will through force. Coaches, myself included, have spent countless hours on fields preaching about getting low, about exploding through the hips. Practices were often dominated by drills that emphasized brute strength and aggressive momentum, operating under the assumption that the most forceful tackler would naturally dominate the play. And while that core idea isn’t completely wrong, new science is telling us we were missing some critical pieces of the puzzle. We were focusing on the engine’s power but ignoring the steering and the brakes. The latest biomechanical research is shifting the conversation from pure aggression to intelligent, controlled collision. It’s giving us a blueprint for a method that doesn’t ask players to be less physical, but to be far more precise.

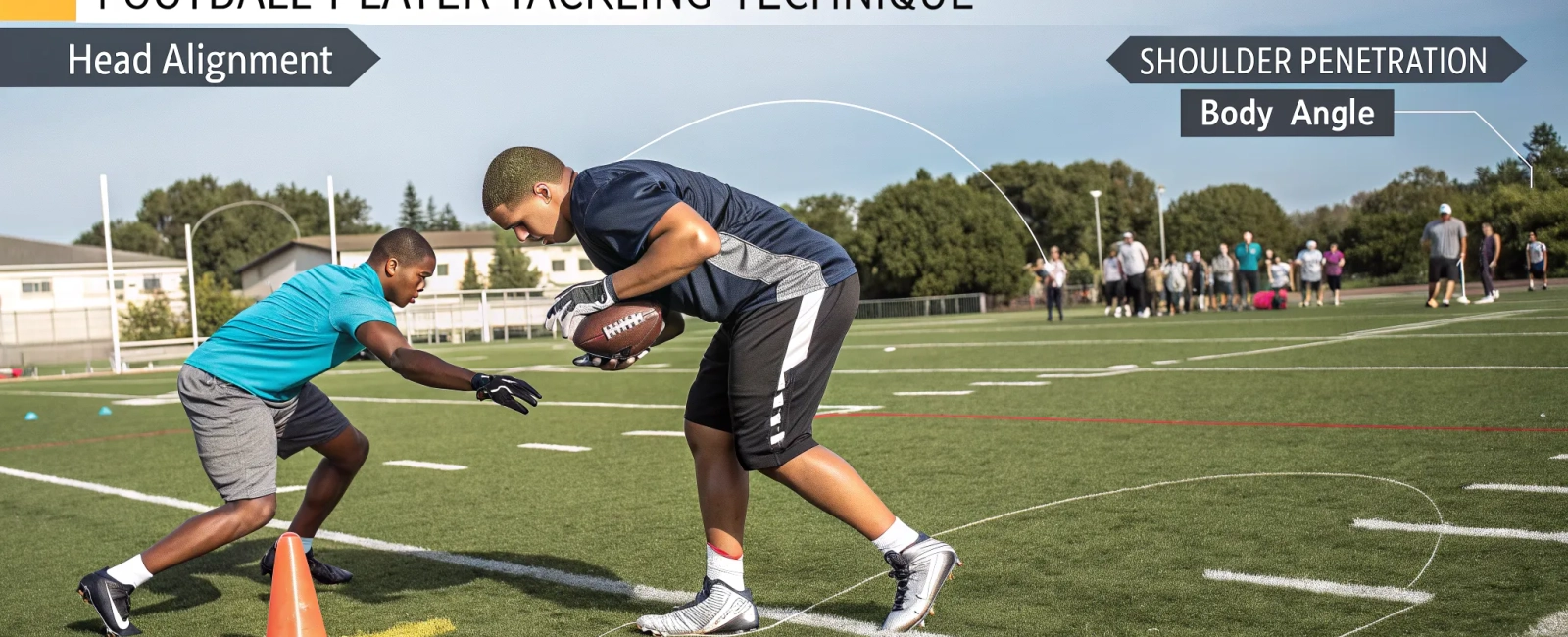

The most significant shift in thinking comes from a study that put young athletes in a lab to measure exactly what happens to their heads during a tackle. This wasn’t about observing games; it was about isolating the action itself under a microscope. Researchers utilized high-speed cameras and motion capture technology to scrutinize each movement and impact in minute detail. They trained a group of players using a specific method that emphasized a vertical, head-up posture. This approach involved not just verbal instructions but also kinesthetic feedback, helping players feel the correct positioning through guided practice. They didn’t just tell them to “keep your head up”—a phrase that’s become a tired, almost meaningless cliché on every field. Instead, they broke it down with video feedback and a detailed scoring system, the QYTS, to show players exactly what they were doing right and wrong. The QYTS included specific criteria such as head alignment, shoulder penetration, and body angle, providing a comprehensive framework for evaluating and improving tackling technique.

The results were impossible to ignore. After just a single day of this targeted coaching, the players showed a measurable drop in the forces acting on their heads. The numbers for both linear and rotational acceleration—the key drivers of concussion—went down significantly. Think about that for a second. Not a season of work, not months of drilling. One day. This tells us that the capacity for safer technique is already there; it’s just a matter of unlocking it with the right instruction. The study identified one of the most critical mechanical adjustments: shorter step length. When a player takes shorter, more controlled steps into contact, they don’t overextend. This adjustment reduces the likelihood of hyperextension or awkward landings that can exacerbate head impacts. They maintain a strong, balanced base that allows their shoulders and core to absorb the impact, not their skull. Their head isn’t swinging like a wrecking ball on the end of a chain; it’s positioned as a stable, protected part of a powerful unit. Additionally, incorporating proper foot placement ensures that the player remains grounded, minimizing the chance of falling awkwardly or losing balance upon impact.

This moves us beyond the old “see what you hit” mantra and into the mechanics of how you hit. It’s the difference between a car crash where one car T-bones another and one where both cars have crumple zones that engage correctly. The outcome is entirely different. In practical terms, this means that tackles become more efficient and less harmful, preserving player health while maintaining the effectiveness of defensive plays. By focusing on the biomechanics of the tackle, coaches can cultivate a style of play that inherently includes safety as a component of effective tackling, rather than treating safety as an afterthought.

So, what does this technically superior tackle actually look like on the field? Another extensive study, which broke down over 800 tackles from high school games, gives us the full picture. The researchers developed a 12-point checklist to grade tackles, encompassing elements such as approach angle, body alignment, shoulder placement, and follow-through. Their analysis revealed that every good tackle follows a clear, three-act sequence: Track, Engage, Finish.

“Track” is where it all begins. This isn’t just running in the general direction of the ball carrier. It’s about closing the distance with controlled, purposeful steps—those shorter steps the lab study confirmed are so vital. It’s about adjusting your path to the opponent’s hips, ensuring that you remain balanced and aligned throughout the approach. Keeping your eyes focused on your target throughout the approach is crucial, as visual tracking ensures that the player can make real-time adjustments based on the ball carrier’s movements. A bad track leads to a desperate, off-balance lunge, increasing the risk of mistimed contact or overreaching, which can lead to missed tackles or injuries. A good track sets the stage for everything that follows, allowing the player to maintain control and readiness for the engagement phase.

“Engage” is the moment of truth. This is where the shoulder-led contact happens. The head-up posture achieved during the track is maintained, and the player drives their facemask across the opponent’s torso, making contact with the shoulder pad. This technique ensures that the force of the impact is distributed across the larger, stronger muscles of the shoulder and chest rather than concentrating it on the neck and head. This is the polar opposite of dropping the head and leading with the crown of the helmet, a technique that turns a player’s neck into a shock absorber for their entire body weight, increasing the risk of concussions and neck injuries. The shoulder-led engage distributes the force across the larger, stronger muscles of the shoulder and chest, absorbing and dispersing the energy more effectively. The study found a direct correlation: higher scores on the engage phase meant a drastically lower chance of any head contact occurring at all. This is the scientific proof that safe technique is effective technique, as it not only protects players but also enhances their ability to successfully bring down opponents without unnecessary risk.

Finally, “Finish” is about completing the job. It’s the vigorous leg drive that continues through the opponent, wrapping the arms and taking them to the ground. A strong finish ensures that the tackle is not only initiated properly but also completed effectively, preventing the opponent from gaining extra yards after contact (YAC). YAC is a key metric for any defensive coach, as it directly impacts the success of defensive plays and the overall performance of the team. This research made the crucial link that better technique doesn’t just prevent injury; it also stops offensive players in their tracks more effectively. By executing a complete and controlled finish, defenders can minimize the opponent’s ability to maneuver and gain advantage, leading to fewer yards gained and more turnovers. There’s no trade-off. You don’t choose between being safe and being successful. The same mechanics that protect a player’s brain are the ones that win possessions for their team, highlighting the harmony between safety and efficiency in modern tackling techniques.

This is where the old-school coaching model gets turned on its head. For decades, the progression was often effort first, technique second. Coaches conditioned players to be tough, to fly to the ball, and we hoped the finer points would follow naturally through repetition and muscle memory. This approach often led to inconsistent tackling forms, with individual players developing their own methods that might not align with safety best practices. The new data argues this is backwards. Throwing a player into contact drills without first building the neural pathways for proper form is like handing someone the keys to a race car without teaching them how to steer. They might go fast, but the crash is inevitable. Instead, the focus must shift to deliberate, methodical training that emphasizes the correct tackle mechanics before introducing full-contact scenarios.

The research suggests that technical training must be separated from the chaos of full-contact scrimmages, especially early on. It needs to start in a controlled, unopposed environment where players can focus solely on mastering the Track-Engage-Finish sequence without the added pressure of immediate physical confrontation. Walk-throughs become essential, allowing players to mentally rehearse the steps and understand the flow of a proper tackle. Repetitive drilling of the Track-Engage-Finish sequence against pads and bags reinforces muscle memory and builds confidence in the players’ ability to execute the technique under pressure. Using video tools to provide immediate, visual feedback is no longer a luxury for professional teams; it’s a fundamental teaching aid that can show a young player what “head-up” truly means in a way a coach yelling from twenty yards away never can. Visual feedback allows players to see their form from different angles, identify areas for improvement, and understand the nuances of each phase in the tackling sequence, leading to more precise and consistent execution on the field.

This isn’t about softening the game. It’s about respecting its physical demands enough to prepare for them correctly. The emphasis on biomechanically sound tackling methods ensures that players are equipped to handle the rigors of the sport without unnecessary risk. It’s about building defenders who are more formidable because they are more disciplined, whose power is channeled and efficient rather than wild and reckless. Such defenders are not only safer but also more effective in their roles, as their technique allows them to leverage their physical capabilities optimally. The science provides a clear, actionable path forward, grounded in empirical evidence and practical application. It’s on us—the coaches and the parents who support them—to move past tradition and embrace an approach that lets kids play hard and, just as importantly, lets them play for a long time. By integrating biomechanical insights into coaching practices, we can ensure that the next generation of football players are both skilled and protected, fostering a safer and more sustainable future for the sport.